I’ve been holding a pencil for as long as I can remember. At first, joyfully. But as I reflect on how drawing has shaped my life, I realize that the reason I draw has changed. It’s lost that initial joyfulness, instead becoming something serious, competitive. A zero-sum game.

Drawing today feels like something you have to win at, or not participate in at all. This essay is an attempt to unpack that, to find the point at which things changed. It might not reflect your own experience, and I really hope it doesn’t! But I hope you’ll be able to recognize some part of yourself in this painful experience. And if you’re a time traveler, reading this in the year 3,000, you have permission to go back in time and assassinate my younger self before they get on Twitter.

As with most kids, drawing was always a social activity. Sitting around the kitchen table with my siblings, making art to make each other laugh. As they get older, most kids stop drawing when they start thinking about what’s “cool” or isn’t, but I kept at it. As a teenager, my friends and I would sit in coffee shops, drawing each other, drawing our dreams, our ideas. The more we drew, the more we improved, but that original spirit — drawing for fun, stayed with us. I think that first changed after I made my Twitter account when I was maybe 17.

Suddenly, I was no longer the best artist I knew. I wasn’t even close! 17 is, by internet artist standards, ancient. You might as well retire. But that didn’t stop me — I now had the forbidden knowledge, and the floodgates had opened — the internet had found me, and I desperately wanted to be a part of it. There’s little you can do as a beginner artist to make you feel more inadequate than to look up “Calarts Sketchbook (Accepted)” on YouTube. That feeling, it’s a hard one to shake.

I’d see my peers online practicing incessantly, and feel silly hanging out with friends. So, I did what I imagined others were doing. I'd come home from school and sit at my desk, filling sketchbook after sketchbook with life drawings, movement studies, and anatomy practice. I'd cancel plans with friends to watch more Proko videos, or copy Mike Matessi’s “Force” page by page. And it worked! I started to understand perspective, form, composition. My drawings became better, my gestures looser. Your hand starts to move on its own, the “S” and “C” curves embedding themselves deep into your bones. “The right side of your back is tense!”, I’d hear from physical therapists for years after.

I got into the college I chose with the highest score, and moved across the continent to join this new group of peers, artists I could learn with. But it didn’t take long to find myself on my own, again. Studying is most effective alone. So, I kept pushing. When I felt ahead of my peers in college, I started looking at graduates, and people in bigger, better schools — how about the people who made those CalArts sketchbook videos? Could I learn to draw better than them? It’s always easy to find someone better than you on the internet.

If you asked me why I was doing it back then, I might have said “I need to draw well to get a good job!”, but that was only partly true. No one draws obsessively from early morning till late at night to get a job.

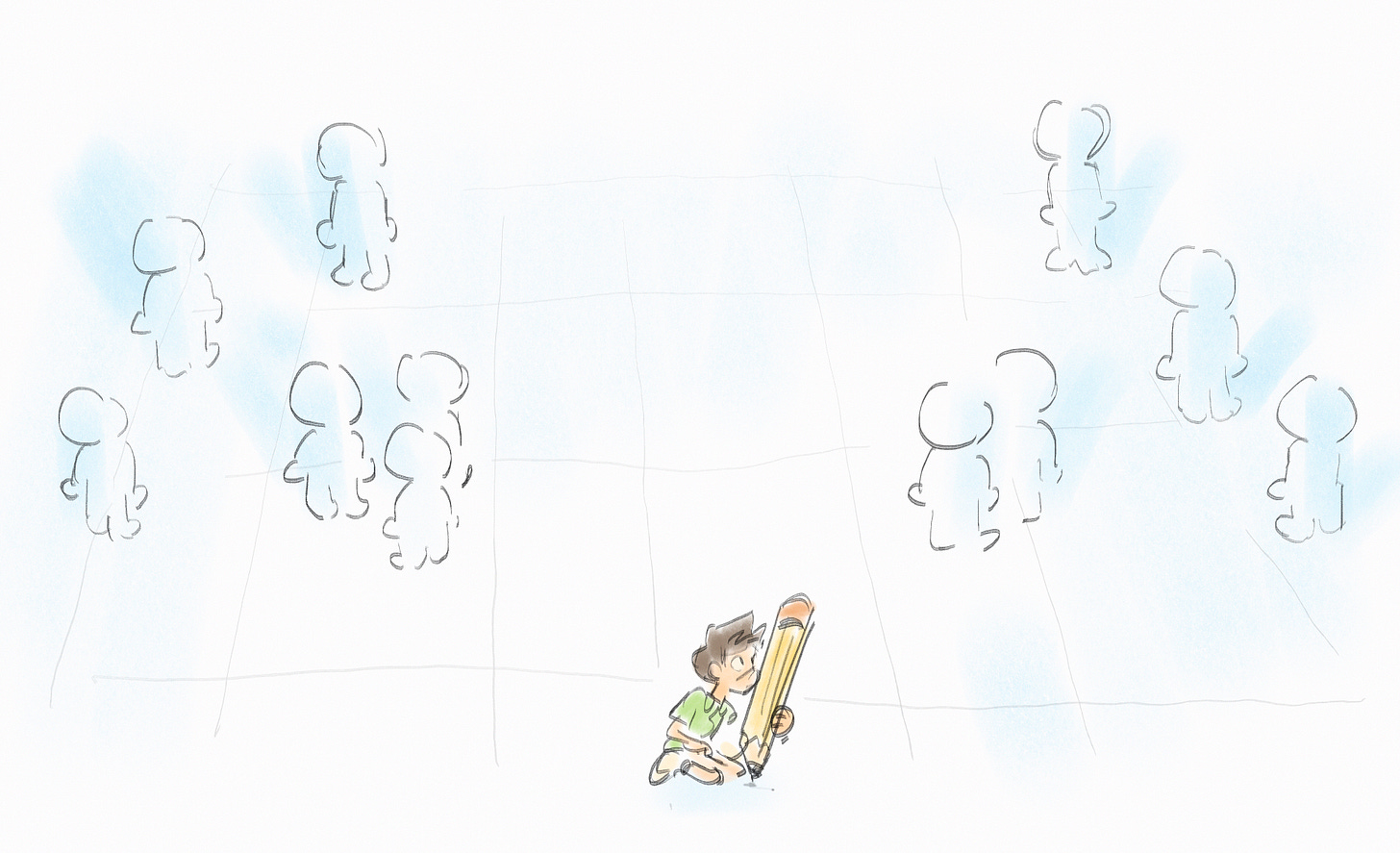

Drawing on the internet is a competitive sport, one like no other. A sport you’re not allowed to talk about, pretending you’re just playing for fun. You silently practice, spending countless hours studying, and only show the best online. You have to make it look easy, like your hand just slipped when the sketch appeared. These invisible rules define online art spaces. You look at speedpaints you’re certain could not possibly have been drawn by a person, and wonder what you’re even doing. The countless hours spent in silent practice remain comfortably out of sight.

As with other competitive sports, privilege plays a bigger role than a casual observer realizes. To be the best at drawing is simple, more of a math problem than a challenge. You just have to spend every moment practicing, from ideally as early an age as you can. The comfort of an upper-middle class upbringing makes this much easier.

You get access to all materials you need, private tutors, expensive portfolio classes. You get to go to a better, more prestigious college, and more time to draw because you don’t need to work a part-time job to pay for it. This unspoken privilege, if mentioned at all, is typically dismissed — “You just need to find the time to practice” is an often seen comment under beginner artist’s posts online. Surely it’s your own fault you don’t have time to draw! You can always sleep less! Skip meals! You can always carve up more of your life to find the time to practice.

Piece by piece, you build your life around drawing. You become devoted, a monk, practicing their faith from dawn to dusk.

As I got older, the friends I sat in that café with all slowly found different passions. Drawing became a day-job or just a hobby. I’ve found that people reach a level of art they’re happy with and drop out of the race, finding things that matter more to them than art. As you get better, only the people who really care remain in the shrinking room. When you find yourself in those uppermost halls of drawing, you’re faced with a choice — do you still want to be the best? How much of your life are you willing to give up for it?

Will you be happy when you reach a height no one else has dared reach before, when you have built a hall atop all others, just for yourself? Loneliness, you decide, isn’t that steep a price to pay for greatness. You push yourself harder and harder, stop sleeping or going out, and then … something breaks. It’s often a wrist, or hand, or something more intangible, but still important — your body tells you, stop. And, if you’re wise, you listen.

When I finally stopped and looked around, I found something I’d lost the moment I got on the internet. A different life, one where loneliness doesn’t have to be the price of greatness. I found myself in a room, surrounded by the people I’d admired from afar. Drawing and telling stories together. Suddenly, it didn’t matter how good my drawings were. All I needed was to have something to say with them. To make my friends laugh.

Drawings, I discovered, are just another tool for communication, one sharpened by practice, but nothing more than that. I felt silly — like someone who’d spent their life writing individual letters, refining the curve of an “a”, or the swirl of a “g”, yet never writing anything more than a sentence with them.

Then, as suddenly as it appeared, that moment passed. As those magical moments always do. These days, I’m in my room again, practicing. But, to be in that room I caught a glimpse of is what I practice for now. Not a hall atop all others, but a great one nonetheless. Filled with people who inspire me, ones who have something to say with their art. You have to be good, your skills sharp, to get in, but those rooms — they’re more common than you think. Because, it turns out, you never needed to be the best one in the room. To be lucky enough to be there is enough.

Thank you to Mish, Sarah, and Christo for reading early drafts of this essay!

My favorite room, currently, is our Discord community! If you are looking for other talented, passionate artists, I’ve found few places on the internet with a higher concentration of them! We’d be delighted to have you!

https://discord.gg/jyGv3ZngMf

Thank you for writing this Wren - it's brave to admit we're all secretly in this race! Because we are. You are totally right in all you said, and un-learning the competitiveness is what I practice now. Just as hard.

And thanks for mentioning the privilege that goes into even an art education - living in South America always made me feel (literally) too far away from "the cool artists", the ones that get jobs and go to CalArts. That's one of the few reasons I stay in the competitive internet space, to find a little "being in the room" equivalent online. Anyway, great post! Difficult topic.