How Hayao Miyazaki builds a story

'And then you start to draw. The story will follow' — Miyazaki Book Club 1

Hayao Miyazaki tells stories like no other director. Each element of the story is a direct representation of Miyazaki’s thoughts put to paper, unbridled by words or structure. In this way, his films offer a rare window into his inner world, and the entirety of production takes on the spirit of its director.

The way he builds his stories is so personal, so wholly unique, and I really believe it’s what lies at the core of his films’ continued success. I’ll be using the production of “Ponyo” as a case study in this essay, but his process looks similar throughout all Ghibli films — a continuous evolution of the same core principles. So, let’s dive in! 🌊

1: And then you start to draw

While most directors begin with a script, Miyazaki approaches the story differently. At the start of production, he has nothing but a hazy idea of what the film will be about — a single illustrative image from which he can build out the rest of the story:

“From within the confusion of your mind, you start to capture the hazy figure of what you want to express. And then you start to draw. It doesn’t matter if the story isn’t yet complete. The story will follow. Later still the characters take shape. You draw a picture that establishes the underlying tone for a specific world.” 1

This is what makes Miyazaki's storytelling different — he sits down and begins to draw without hesitation. After all, can a single image not convey 1000 words?

“What rushes forth from inside you is the world you have already drawn inside yourself, the many landscapes you have stored up, the thoughts and feelings that seek expression”

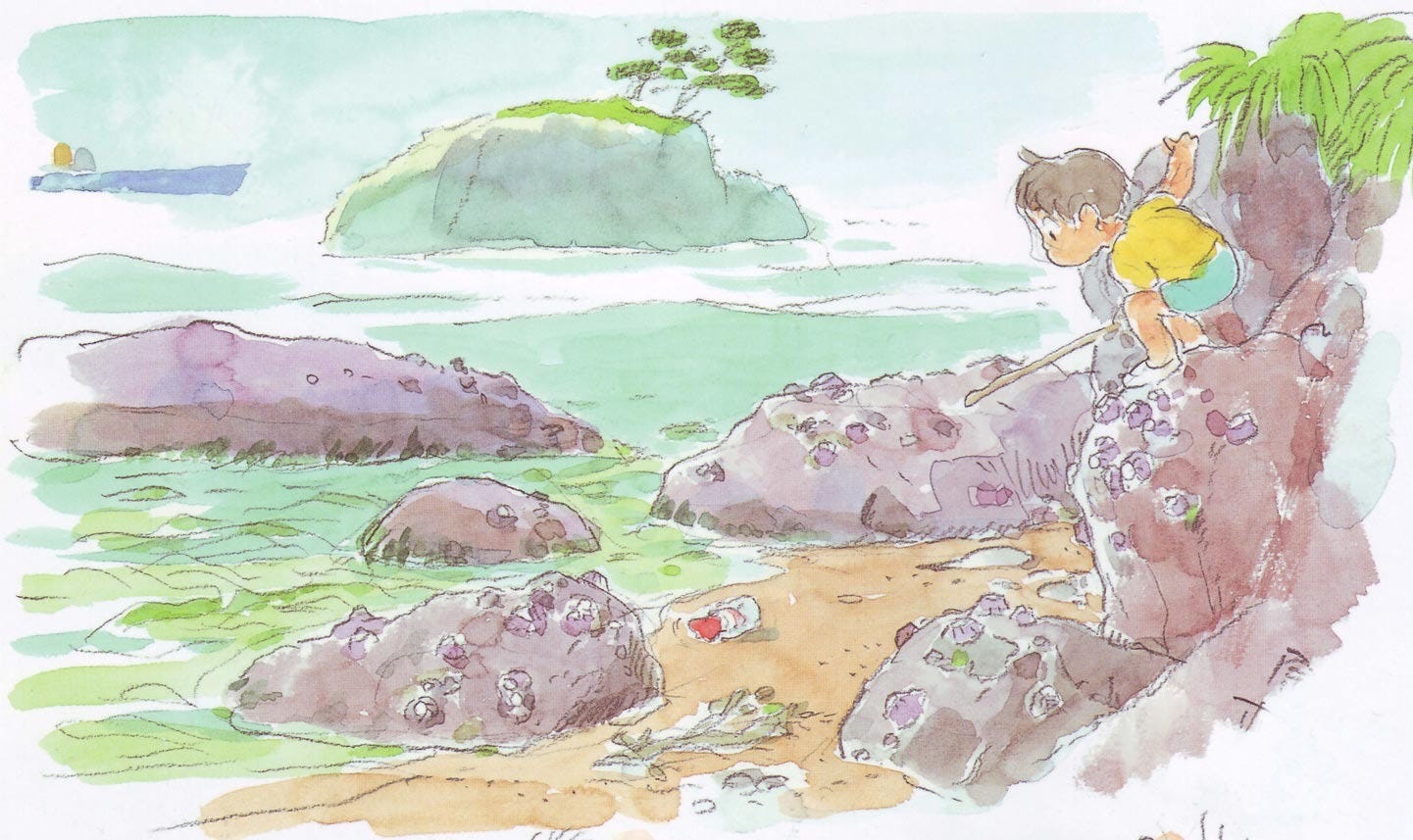

He draws a series of ‘image boards’ — rough sketches on large sheets of paper capturing the main events of the story.2 As he finishes each one, he hangs them up on a communal wall for the team to see and discuss. While drawing the beats of the film, the characters begin to take shape. Some were in the original drawing, while others are formed to support the story. The image boards build out the narrative, revealing which elements work, which don’t, and what needs to change or be rearranged.

Rather than starting with a complete narrative, he lets it unfold organically. His goal is to imbue each beat with strong emotion, rather than following a pre-determined structure. The beats need to link to each other consecutively, but the way they connect isn’t important — those empty gaps left between each key moment end up serving the story through what he calls “Ma” — the empty space between moments of action.3

So, if not a structure or a script, what drives his work — what pushes him on from one image to the next? “Surprise, total discovery, therefore seem to be at the heart of Miyazaki’s poetic journeys even within the seemingly most everyday environments”.4

Characters shift and morph, and the story itself begins to take shape as he’s looking for it’s core — an emotional truth he can express. In ‘Ponyo’, the core is simple: “A little boy and a little girl, love and responsibility, the ocean and life”.5

2: The trunk of the story

“What catches the audience’s eye is the treetop, the shimmer of the leaves … One must have the clear core of what he wants to convey. This is the trunk of the story”

This is the 'core' of the story, its theme. A common approach among directors is described by Brian McDonald — "you have to have something to say, something you've learned about yourself, about being human. But it has to be true — emotionally."6 However, where other directors would approach this by applying structure to the story, Miyazaki seems a little more comfortable with the discomfort of not knowing where it starts or ends.

What’s interesting is that he’s never ‘writing’ — his stories could only ever exist as films. He’s not just dressing up words in imagery, he is building out the story one image at a time. There’s dialogue, but the animation is at the heart of the film. The acting isn’t just a vehicle for the plot — it is the plot. Characters are free to act and react to their environment and each other’s actions, and they seem to have free will to act on the world through the screen.

While there’s definitely room for improvisation and character expression at other studios and production methods, here it lies at the very center of production. It’s how Miyazaki is able to build out entire sequences with no dialogue, or create characters that resonate so much with audiences. It’s the empty spaces, “Ma”, that allow for such endless possibilities between significant moments.

3: Writing logical lines for old men

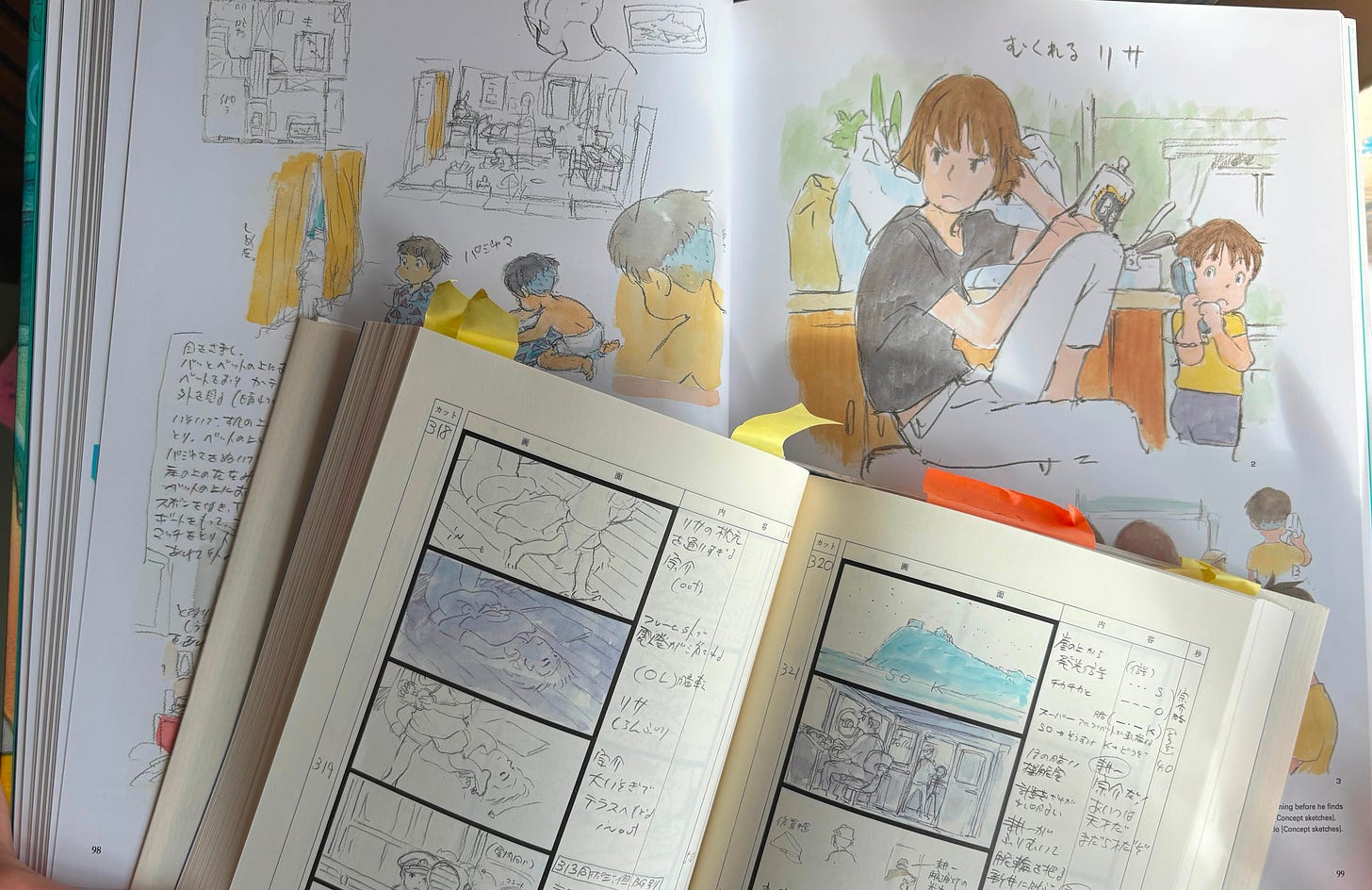

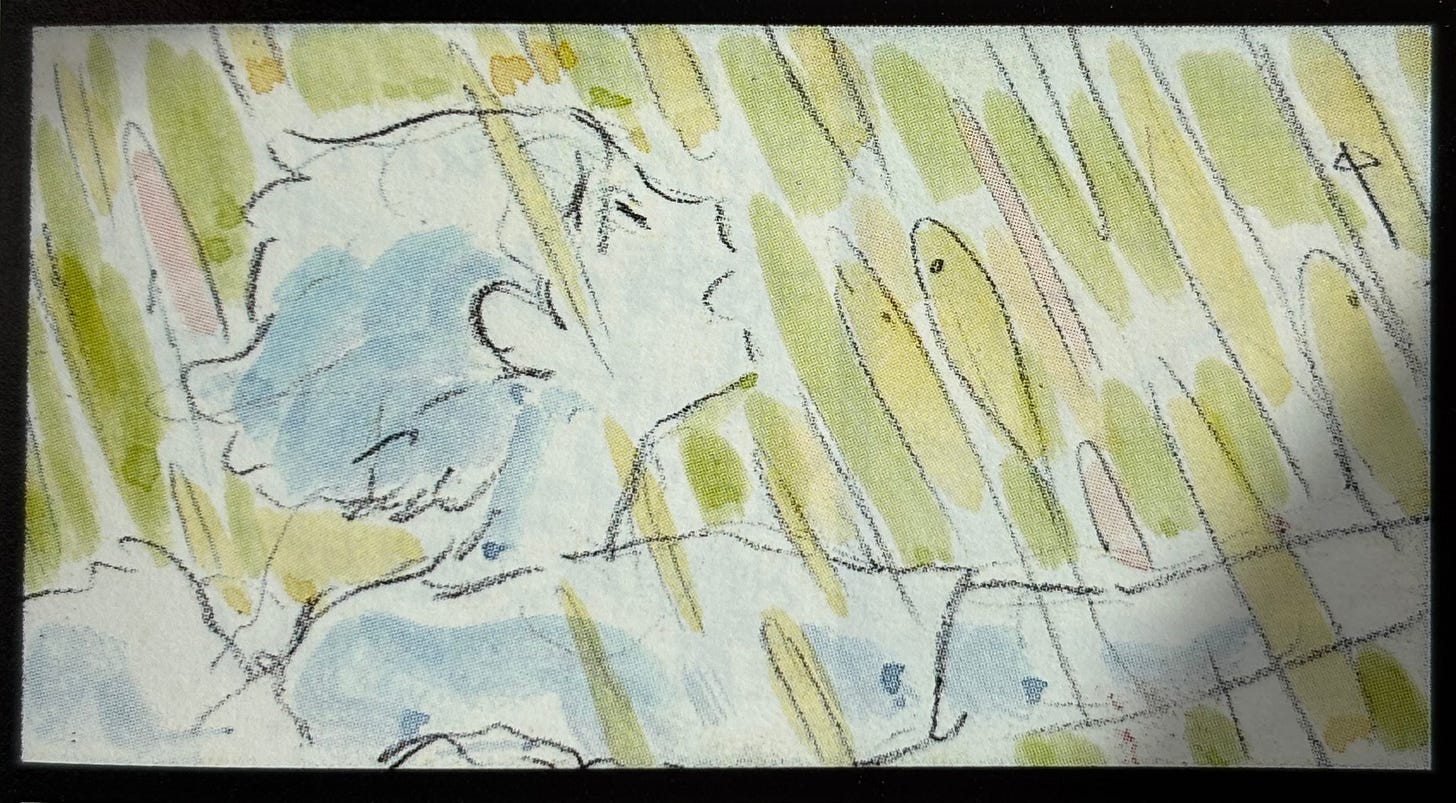

After finishing the image boards, Miyazaki begins storyboarding and the film enters production: “Using his powers of continuous concentration, the production starts to take on the elements of an endlessly improvised performance”. There’s no time for revisions; Miyazaki is so confident in his decisions that storyboards are sent into animation as soon as they are completed. At the same time, they’re left vague and open to interpretation, giving animators the freedom to express themselves through the characters.

As he storyboards, Miyazaki is constantly putting himself in his characters’ heads: “what would a 5-year-old do? (it’s) meaningless, writing logical lines for old men”. He chooses to portray the world as seen through the eyes of his protagonists. He has an idea of where the story is going, but the moment-to-moment is all dictated by improvisation. “He wants to encounter scenes that he has never imagined before”.7

This creates a film that is given free rein to change and evolve as it goes on, with animators and other production staff shaping the film almost as much as Miyazaki himself. He, for one, seems happy with this:

“The reality is that only as I work on a film do I, myself, gradually come to understand the content of the film. That is why I consider films not to be something I am making, but something that is the result of mixing many different elements together. (…) I don’t have the sense that “my own ideas are at the core.” It is very nebulous as to whether it was my idea or whether someone else’s idea came flowing in.” 8

Maybe this is what makes Studio Ghibli films so memorable — they’re films that could only exist in animation, reflecting the process and efforts of the people who make them. When I started researching this essay I had a single, limited idea of what an animated production is supposed to look like: after all, most studios use a similar process. But I now have this sense that we’re only now starting to discover what animation is, and how the process we follow ends up shaping the films we create.

This all feels distinctly ‘Miyazaki’ — in making stories about characters pursuing freedom and seeking to improve the lives of others, the films themselves seem to embody Miyazaki’s own pursuit.

🌟 Hey, thanks for reading this essay! This was probably the most ambitious one I’ve written — I really hope you liked it! It’s the first part in a series on Miyazaki’s storytelling I’m calling Miyazaki Book Club. The next one is a narrative analysis of “Ponyo”, and the rest will cover pacing, narrative structure, Miyazaki’s thoughts on the purpose of animation. I'll be releasing one every two weeks for the next 2 months, so I hope you'll follow along! :-)

For more on this, I recommend looking through the Ghibli storyboard books, some of which you can see here!

10 Years with Hayao Miyazaki: The Making of Ponyo, Dir. Kaku Arakawa

I’ll write about this more in the next essay of the series - stay tuned!

Animated Geography: The Experience of the Elsewhere in Hayao Miyazaki’s Work, by Emmanuel Trouillard

From the film’s original studio pitch, found in ‘Turning Point: 1997-2008’ by Hayao Miyazaki

Invisible Ink by Brian McDonald - my favorite book on screenwriting!

Toshio Suzuki, NHK Interview

From ‘Starting Point: 1979-1996’ also by Hayao Miyazaki

Wonderful piece! The 10 Years with Miyazaki NHK series absolutely gutted me- specifically, his troubled relationship with his son, Goro. Goro said he would watch his father’s films to know him. The line that still stays with me is when Miyazaki said, “I owe an apology to that little boy.”

Thanks for this. This felt like a fly-on-the-wall kind of insight into Miyazaki's process. Whenever I watch one of his films next, this will be at the back of my head.